3rd World Farmer was available in Spanish for a time, and I hope the translated version returns. It would be an excellent at-home complement to farming, finance, or even family vocabulary units, reinforcing the material while also promoting strategic thinking and global awareness.

Monday, March 24, 2014

More Gamification: Serious Games

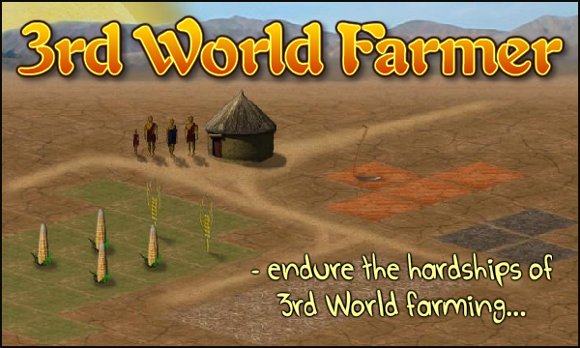

In my last post, I wrote about playing games for education in the classroom. This time, I want to talk about games that students can play at home. I found one called 3rd World Farmer that does a great job illustrating the hardships faced by people in certain other areas of the world. The player controls a family struggling to succeed on a farm under harsh conditions, battling drought, sickness, civil war, and a slew of other calamities. Each turn in the game covers a year, meaning that one game might span generations - if you're lucky. 3rd World Farmer is a relatively simple, but brutally difficult game. I played at least a dozen times, and most of my families died out before achieving success.

3rd World Farmer was available in Spanish for a time, and I hope the translated version returns. It would be an excellent at-home complement to farming, finance, or even family vocabulary units, reinforcing the material while also promoting strategic thinking and global awareness.

3rd World Farmer was available in Spanish for a time, and I hope the translated version returns. It would be an excellent at-home complement to farming, finance, or even family vocabulary units, reinforcing the material while also promoting strategic thinking and global awareness.

Gamification and the Mystery of Time and Space

Gamification is a quickly growing trend, in which an activity is given game elements to turn it into - you guessed it! - a game. Games can be powerfully motivating, and indeed, gamification is most often used as a motivational strategy: it can be used to hook people on a product or service, to promote behaviors like recycling, or even to motivate students in an educational setting. Obviously, this last is the one I'm most interested in.

I recently played a game called Mystery of Time and Space (MOTAS), which is an escape the room-style point-and-click game in which players need to manipulate the objects in a locked room in order to escape and move on to the next room. When the mouse is held over an object, its name appears, and clicking it earns the player a description.

Games like this are often used in classrooms to practice language skills. MOTAS is especially popular, and there are a number of resources like this one to guide teachers in integrating it into their classrooms. It is available in a variety of languages, including Spanish, making it a useful tool in any language classroom.

I might employ a lesson in which students must find every object in a room and write a short description for each, with the goal of expanding and practicing vocabulary in a more authentic setting than a textbook can provide. Once that has been done, students could be given a walkthrough to follow (a list of the steps to take in order to complete or escape the room), which would allow them more practice and me an opportunity to gauge their comprehension skills.

I recently played a game called Mystery of Time and Space (MOTAS), which is an escape the room-style point-and-click game in which players need to manipulate the objects in a locked room in order to escape and move on to the next room. When the mouse is held over an object, its name appears, and clicking it earns the player a description.

Games like this are often used in classrooms to practice language skills. MOTAS is especially popular, and there are a number of resources like this one to guide teachers in integrating it into their classrooms. It is available in a variety of languages, including Spanish, making it a useful tool in any language classroom.

I might employ a lesson in which students must find every object in a room and write a short description for each, with the goal of expanding and practicing vocabulary in a more authentic setting than a textbook can provide. Once that has been done, students could be given a walkthrough to follow (a list of the steps to take in order to complete or escape the room), which would allow them more practice and me an opportunity to gauge their comprehension skills.

Monday, March 10, 2014

Twitter for Teaching

My last post focused on some of the issues I have with Twitter, most of which can be much more briefly summed up by #1 on this list: 10 Twitter Mistakes You Should Avoid.

Another list, however, describes an awful lot of things Twitter is good for: A Must-Have Guide to Using Twitter in Your Classroom. My personal favorite is under Communication: "#11: Stay on top of the learning process: Ask students to tweet and reply about what they’re learning, difficulties they’ve faced, tips, resources, and more as an online logbook." This is a good trick, and unlike some of the others, it's not one that can be easily duplicated with e-mail. Getting students communicating and involved in their own learning can be powerful, and connecting to them by engaging them using social media networks they likely already use is a good way to get that started. #14: Teaching Bite-size Info is also a good one. Tweets are perfect for sharing the small things that are bound to get left out of the lesson on occasion. These bites should be interesting and relevant so that students find them valuable, but any vital information should be covered in class. Treat them like treats, and encourage your students to do the same.

Another list, however, describes an awful lot of things Twitter is good for: A Must-Have Guide to Using Twitter in Your Classroom. My personal favorite is under Communication: "#11: Stay on top of the learning process: Ask students to tweet and reply about what they’re learning, difficulties they’ve faced, tips, resources, and more as an online logbook." This is a good trick, and unlike some of the others, it's not one that can be easily duplicated with e-mail. Getting students communicating and involved in their own learning can be powerful, and connecting to them by engaging them using social media networks they likely already use is a good way to get that started. #14: Teaching Bite-size Info is also a good one. Tweets are perfect for sharing the small things that are bound to get left out of the lesson on occasion. These bites should be interesting and relevant so that students find them valuable, but any vital information should be covered in class. Treat them like treats, and encourage your students to do the same.

Twitterchats

I recently attended #edtechchat on Twitter. The conversation focused on the benefits and drawbacks of online learning, face-to-face learning (f2f), and blended approaches. Moderators started discussions with questions (coded Q1, Q2, etc.) and participants used their 140 characters to share their thoughts (coded A1, A2, etc.).

I have to be honest: I am not a fan of Twitter. I had hoped this chat would change my mind, but I don't think Twitter's format lends itself to any kind of organized discussion. Instead, it encourages a sort of free-for-all, just like a classroom with a hundred students where nobody needs to raise their hand or wait for anyone else to stop speaking. Regardless of whether anyone actually has anything good to say, 140 characters is almost always too few to construct a meaningful response, and I always find myself completely overwhelmed by the sheer number of tweets being produced, even using the search function to sort by hashtags.

What I did take away from the conversation was a bunch of Twitter accounts worth keeping track of. This is where Twitter really shines. In my opinion, Twitter works best as a tool for sharing ideas in one direction at a time: a user who consistently makes interesting or useful individual posts is one to follow and learn from. A user who participates in large-scale conversations will likely dilute their feed with posts that quickly become meaningless or impossible to understand when removed from that context. While the appeal of the latter suffers from being difficult to follow, I think that a thoughtfully managed account of the first type can be an excellent tool for professional development.

I have to be honest: I am not a fan of Twitter. I had hoped this chat would change my mind, but I don't think Twitter's format lends itself to any kind of organized discussion. Instead, it encourages a sort of free-for-all, just like a classroom with a hundred students where nobody needs to raise their hand or wait for anyone else to stop speaking. Regardless of whether anyone actually has anything good to say, 140 characters is almost always too few to construct a meaningful response, and I always find myself completely overwhelmed by the sheer number of tweets being produced, even using the search function to sort by hashtags.

What I did take away from the conversation was a bunch of Twitter accounts worth keeping track of. This is where Twitter really shines. In my opinion, Twitter works best as a tool for sharing ideas in one direction at a time: a user who consistently makes interesting or useful individual posts is one to follow and learn from. A user who participates in large-scale conversations will likely dilute their feed with posts that quickly become meaningless or impossible to understand when removed from that context. While the appeal of the latter suffers from being difficult to follow, I think that a thoughtfully managed account of the first type can be an excellent tool for professional development.

Monday, March 3, 2014

Language Practice Hangouts

I just found Language Practice Hangouts (https://plus.google.com/communities/117021348126795052161) - a community page dedicated to connecting language learners for chats and practice! As it says on their page, you can "Hangout and practice your language skills with native speakers". You have to request membership (I'm currently waiting on a "yes"), but the vibe is friendly and inclusive. Members organize group hangouts and help each other practice skills in 18 different languages. I love that there are people and resources (often the same thing - see previous post) like this!

Learning at the Subatomic Level

A learner is like an atom. At its core is the physical body, the brain, the person itself, a nucleus of protons and neutrons and internalized information: what the learner actually knows. Floating in a hazy cloud around this nucleus is an electron field, composed of information that is easily accessible to the learner: his or her immediate network.

Few atoms are satisfied with their own electrons, however, and many create a variety of bonds with other atoms to form larger molecules and accomplish far more than each could individually, in a wholly unique way that never would have occurred to any of the atoms on its own. In the same way, human beings share their knowledge pools and form networks of information, sharing and trading for a similar gestalt effect. Without the outward projection of ideas, however, their could be no learning process; much like an atom without electrons, we would be stable, or stagnant. A learner must have an immediate network before they can connect to a larger one. As connectivist theorist George Siemens says: "We ourselves need to externalize our thoughts, in order for us to have the ability to connect with other individuals" (The Conflict of Learning Theories with Human Nature: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTgWt4Uzr54&list=PL3E43054A8703F57A&index=3).

But by reading this post, you have joined (and hopefully benefited from) my own small network, which became part of a larger network (the hosting website) the moment I posted it. The fact that you have learned to successfully navigate the tremendous super-network of the internet in order to arrive at this page will be more instrumental to growing your personal learning cloud than anything I could possibly teach you. According to Siemens: "The pipe is more important than the content within the pipe", which he explains as meaning that a person's ability to learn what they need to know is far more useful than what they actually know (Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age: http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm). For a third metaphor, pretend learning is like driving a car. It doesn't so much matter where your car is currently parked; as long as you have the appropriate networks (in this scenario, a well-laid road system), you can get anywhere you need to be.

Few atoms are satisfied with their own electrons, however, and many create a variety of bonds with other atoms to form larger molecules and accomplish far more than each could individually, in a wholly unique way that never would have occurred to any of the atoms on its own. In the same way, human beings share their knowledge pools and form networks of information, sharing and trading for a similar gestalt effect. Without the outward projection of ideas, however, their could be no learning process; much like an atom without electrons, we would be stable, or stagnant. A learner must have an immediate network before they can connect to a larger one. As connectivist theorist George Siemens says: "We ourselves need to externalize our thoughts, in order for us to have the ability to connect with other individuals" (The Conflict of Learning Theories with Human Nature: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTgWt4Uzr54&list=PL3E43054A8703F57A&index=3).

But by reading this post, you have joined (and hopefully benefited from) my own small network, which became part of a larger network (the hosting website) the moment I posted it. The fact that you have learned to successfully navigate the tremendous super-network of the internet in order to arrive at this page will be more instrumental to growing your personal learning cloud than anything I could possibly teach you. According to Siemens: "The pipe is more important than the content within the pipe", which he explains as meaning that a person's ability to learn what they need to know is far more useful than what they actually know (Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age: http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm). For a third metaphor, pretend learning is like driving a car. It doesn't so much matter where your car is currently parked; as long as you have the appropriate networks (in this scenario, a well-laid road system), you can get anywhere you need to be.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)